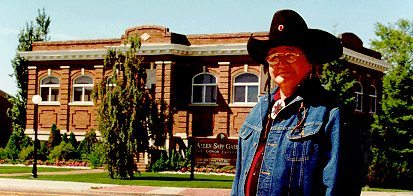

About the Allen Sapp Gallery:

ALLEN SAPP: HIS STORY

Allen Sapp was born in the winter of 1928 on the Red Pheasant Reserve in north central Saskatchewan. He was a weak and sickly child born to a mother who herself had to fight for her life and who eventually died of tuberculosis. Allen was raised and cared for by Maggie Soonias, his grandmother. The memory of this tender relationship has spawned in Sapp some of his finest and most sensitive works, bringing to his canvas a sense of affection and love rarely communicated or seen in the twentieth century art world.

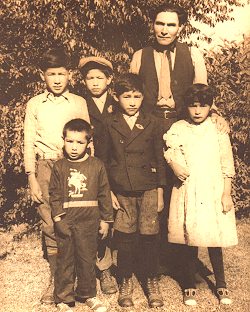

Family portrait was taken in Prince Albert, Saskatchewan. Allen and his family had to visit his mother who was in the sanatorium at the time. Pictured are : Allen's father, Alex, Allen (with hat), brothers John, Henry, Simon and sister Stela. |

Allen was often sick as a child and was picked on by other children. He never learned to read or write but found refuge and satisfaction in drawing pictures. When he was eight years old and suffering again from a childhood illness, the Nootokao (old matriarch) had a dream in which Allen was threatened seriously with death. She was compelled to bestow a Cree name upon him. She touched his forehead as he slept and called him Kiskayetum (he perceives-it). |

|

As Allen grew older he grew in this gift of perceiving and more and more found great satisfaction in painting and drawing. At the age of fourteen he was stricken with spinal meningitis. The recovery from this near fatal illness was slow and exhausting, but the Nootokao had promised he would not succumb to illness, but live to make Naheyow (the people) proud of him and become a blessing to both the Naheyow and the white race. There was a purpose for this frail one who made such a determined effort to live. One day he would be instrumental in communicating what could never be said in words; a message to people, white, Indian and eventually through the world over; a message that tells the viewer of the quiet and gentle people and their determined struggle to survive in a harsh and unforgiving environment during the Great Depression. By 1945 the depression had taken its toll on Allen's own family; four of his seven brothers and sisters had died including Allen's favorite brother John who died of tuberculosis at the age of thirteen. The deaths, Allen's own grave illness and the poverty of all combined to make Allen want to leave the reserve and live in North Battleford. It would be over a decade before he could make the move. In 1955 Allen was married. His wife spent several years in the Tuberculosis Sanatorium in Prince Albert. It was there in 1957 their son David was born. Sapp's sensitive depiction of his own people and their passing way of life has not always been the subject of his canvas. In his effort to survive as an artist, Allen struggled with many things from the content of his painting to his own identity as a Cree. It was between 1961 and 1966 that this struggle reached its peak. Allen, his wife and son had moved from the reserve into North Battleford and rented a humble upper story of a house. In this flat Allen set up his easel and began to paint. It was here, Allen was sure, he would be able to provide for his family as an artist. While peddling his paintings on the street, in an effort to gain prominence and respectability in a white man s world, Allen had changed. His hair was short, he wore ill-fitted suitcoats and black horn-rimmed glasses. Although he could speak very little English, his image had been tailored to what he felt the white man would accept. His paintings themselves denied the past and had become mostly calendar art with mountains and streams and animals Allen had only seen in pictures. This effort to satisfy a fickle white culture in order to survive began to erode the essence of who Sapp was and tear away at the true and authentic experience of his Cree ancestry. |

|

| One winter morning in 1966, Sapp ventured timidly into the North Battleford Medical Clinic trying to sell his paintings to the doctors. There he met the clinic's director, Doctor Allan Gonor. This meeting was to begin a relationship that would change both men's lives. Allan Gonor immediately saw a depth and possibility in Sapp's work that fascinated him. It was on Allen's second visit to Doctor Gonor that the painting of Chief Sam Swimmer caught his eye. He bought it at once and gave him a little extra money for supplies. "This is much better," I told him, "you should paint what you know, you are a Cree Indian." Doctor Gonor asked Allen if he would paint more of the people and places he remembered from the reserve and in so doing opened the door to a place in Allen Sapp's soul. At first the paintings seemed to just pour out. | |

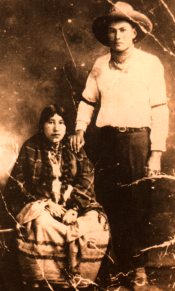

| Doctor Gonor had hoped to buy what Allen could produce but quickly realized that Allen was painting one or two paintings a night. Doctor Gonor began to seek advice from professionals across Canada in order to assist Allen. It was not without reservation that Sapp was painting the memories of his past, for he had come to know the cynical nature of the white man and was deeply afraid that he and his people would be laughed at. It was through the encouragement of people like Wynona Mulcaster, an art professor at the University of Saskatchewan, that Allen's fears were soothed. Doctor Gonor had arranged to drive Allen to see Wynona upon the advice of the director of the Winnipeg Art Gallery, Doctor Ferdinand Eckhardt. After many of those trips and many discussions about content and technique, Wynona and Doctor Gonor felt Allen had begun to grasp the value of his roots and the virtue of his past as it really was. | Allen's Mother and Father. Date unknown.  |

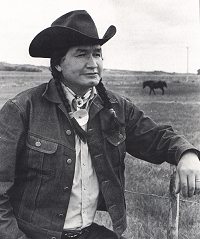

In September of 1968, Wynona invited Allen to show his paintings on the grounds of her home in Saskatoon. In spite of the weather, the show was a great success, but this favorable response from a largely artistically cultured crowd in no way prepared them for the overwhelming public response to his first major exhibition only seven months later. It was Easter weekend at the Mendel Art Gallery in Saskatoon; a show of sixty-one oils and acrylics had been assembled and hung. When the doors finally opened that weekend some 13,000 viewers passed through the gallery. At the conclusion of opening night most of the sixty-one paintings had been sold. That Easter weekend in 1969 began an explosion of interest and fascination with Sapp's work that resulted in shows from London, England through to most major cities in Canada and cities in the United States including New York and Los Angeles. Allen Sapp had come of age. Reviews on his shows came from all quarters. He was applauded by the public as a 20th century painter they could relate to and by the critics as a painter whose style created "illusionism so arresting as to constitute a revelation". (Daily Telegraph of London, 1969). By now Allen himself had begun to grasp the full implications of his success, but his reaction was modest and in character. He had found in painting his memories and his people a sense of pride in who he was and where he had come from and so began his own journey in becoming the Cree Indian he had discovered within. Allen had begun to discard his white man's appearance. He let his hair grow into long braids that he tied up with deerskin. He began to wear denim cowboy boots, beaded medallions and a headband along with his cowboy hat. He was a descendant of the great Chief Poundmaker and had begun to understand the pride of being able to live that. It was during that period that Allen observed simply "better to be a good Indian then a poor white man." So Allen became that "good Indian", but fate also held that he was to become an Indian of central importance to the preservation and renaissance of his own culture. In May of 1976, Allen visited New York to attend the opening of h s show at the Hammer Galleries. Diana Loercher of the Christian Science Monitor observed of Sapp and his work, "He had great reverence for the land, a tradition in Indian Religion, and derives much of his inspiration from nature. A radiant light permeates most of his paintings.... It is evident that not only his art but his identity is deeply rooted in Indian culture." It was this deeply-rooted identity that acted to stabilize Allen during these years of great attention and ensured his values and priorities remained true. As Doctor Gonor observed: ''His values have not changed. Because of the traditional Indian belief in sharing, he uses his car as a taxi and cares more about participating in religious ceremonies and dances then painting. Even though he cannot keep up with the demand." The significance of Sapp's return to his roots and the stability and vision it offered him cannot be understated. But aside from Sapp's own heritage the other important influence and stabilizing factor in his life was the deep and wonderful friendship that grew between himself and Doctor Allan Gonor.

" He let his hair grow into long braids that he tied up with deer skin" "fate held he was to be an Indian of importance to the preservation and renaissance of his own culture ". |

To the outside observer, the importance of the Sapp-Gonor relationship became largely overshadowed by the emergence of Sapp himself. At each new show the focus became more clearly fixed on Allen Sapp, his gift, and its value to all Canadians. In Ottawa, then Indian Affairs Minister Jean Chretien stated, "He has made a great contribution to the cultural background of his own people." Others described Sapp's work as "a story (of his people) more vivid on canvas than has been told by hundreds of printed words... he must be credited with having already done a real service to his people..." (Saskatoon Star-Phoenix). "Allen has developed a powerful language that communicates better than words," observed Winona Mulcaster and what was equally important was the timeliness of his message. |

| By 1974 Allen Sapp had found commercial success and had attained widespread attention. He had been the subject of a book Portrait of the Plains by then Lieutenant-Governor of Alberta, Grant MacEwan. His life and art was also the subject of a CBC and a National Film Board documentary, and he had met a number of important people including the Prime Minister, Pierre Trudeau. All of these events gave evidence of his popularity and the respect he had gained as an artist, but little did he know he was about to experience one of his greatest milestones as an artist. | |

In December 1985, Allen Sapp was elected to the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts (R.C.A.A.). Election to the R.C.A.A. means something far beyond commercial success for an artist. The historic role pursued by the R.C.A.A. through the years has been to maintain the highest standards in the cultivation of the fine and applied arts in Canada. Members of the R.C.A.A. represent a cross-section of Canada's most distinguished artists. Election to membership is the acknowledgment of the quality and value of Sapp's work by one of the most demanding and discriminating groups concerned with the arts in Canada, his own peers. As each new award or acknowledgment came, Allen's reaction remained modest and simple. In 1980 he met Princess Margaret and presented her with one of his paintings. In 1981, a book A Cree Life The: Art of Allen Sapp was released and found its way across Canada as a very popular bestseller. These and many other events all helped to maintain the focus on Sapp's contribution as an artist. 1985 was the year that began a subtle but important change in what was to be the way his contribution as an artist was viewed. It was this same year he was to face the news that his good friend and patron, Doctor Allan Goner, had died while visiting in Thailand. Allen Sapp, from a very early age, had come to know and experience the death of others as an inevitable part of life. He, himself, had experienced the death of many members of his own family and had struggled deeply with the loss of loved ones. It was his determination and strength of character that seemed to guide Allen through these difficult times. This strength of character made Allen not only a good and valued artist but a person of exceptional value to his whole community. It was that aspect of Allen's contribution which began to emerge and the community that was to call him their own began to expand far beyond the bounds of the Red Pheasant Reserve or the City of North Battleford. On December 5, 1985, Allen Sapp became one of the first eight recipients of the Saskatchewan Award of Merit. This award is given in recognition of individual excellence and/or contributions to the social and economic well-being of the province and its residents. It was one of the first indications that Allen Sapp's contributions, not only as an artist but as an individual, were being felt. There was a building awareness that somehow Sapp's contributions were not just limited to exceptional art. He had become recognized as a significant force in the renaissance of the Indian culture. His art clearly had the ability to cross cultural barriers and, not only acted as a beacon for aspiring native artists, but also as a vehicle for other cultures to comprehend the Indian way of life.

December 5, 1985 Allen Sapp receives the Sask. Award of Merit. " The community that was to call him their own began to expand far beyond the Red Pheasant Reserve." |

Governor General Jeanne Sauve presents Allen with the insignia of membership in the Order of Canada. |

It came as no surprise that in 1986, at the "New Beginnings" Native Art Show in Toronto, Allen Sapp was singled out as one of the Senior Native Artists in Canada, "whose contributions to the present renaissance of native art and culture will only be measured by history." That simple observation seemed almost prophetic in light of what was about to occur. In January 1987, the Governor General of Canada appointed Allen Sapp an Officer to the Order of Canada as a means of recognizing outstanding achievements and honoring those who have given service to Canada, to their fellow citizens or to humanity at large. After more than half a century, the prophetic words spoken by the Nootokao, who had placed her hand upon his forehead as Allen lay sick, had now come to pass. "'There was a purpose for this frail one, who made such a determined effort to live.... He had made the Naheyow proud of him and had become a blessing to both the Naheyow and the white race." The opening of the Allen Sapp Gallery: The Gonor Collection is truly but another page in what has become one of the most fascinating stories in Canadian Art History. The importance of the gallery as a signpost for aspiring artists and as a vehicle in the promotion and conservation of our Canadian heritage cannot be overstated. But possibly the most important role this gallery will play through the art of Allen Sapp is to provide a bridge for healing and quiet dialogue between white and native cultures thereby creating a deep understanding and respect not otherwise possible.

|

" If you lose money you can get it again. |

| - ALLEN SAPP |

" The paintings of Allen Sapp reveal what a reservation

means to those for whom it is home. Like Remington

and Russell in the United States before him, Sapp is a

historical chronicler of a life and society that will pass

into history, recorded with the sensitivity of one who

was part of it. With honesty and without embellishment

the artist depicts a bleak environment in a harsh climate

without trace of bitterness or protest. "

Zachary Walter Gallery

Los Angeles, California

Sapp's canvases, more than any other Canadian artist, center on family and community. Even when a canvas does not contain a single person, its title or content alludes to the presence of individuals who make up an intimate part of its memory. Many have observed Sapp's extraordinary ability to paint the landscape and natural world around him. Max Wykes-Joyce (Art in London) saw Sapp as having "an acute visual perception . . . a feeling for the land and for the life of the land is a part of the artist's subconscious inheritance." It is this life of the land that so intricately connects it with the people who draw life from it. Sapp's works reflect the deep value his people hold in the land, but it reveals even more sensitively the value the Cree see in all living things and especially human life. To the Cree, nature, human life, family and community are all intimately connected. It is for this reason that upon viewing Sapp's work one seems to enter into a deeply personal world that leaves the viewer with a sense of privilege in what is being shared with them. As we discover just how Allen Sapp paints and learn more about what his paintings can reveal to us, our sense of privilege deepens and the mystery of his gift begins to unfold.

The Memories of a Child

Allen Sapp's approach to painting is totally unique. There may only be a handful of artists in the world today who paint as he does. Although it is difficult to describe in words, Allen seems to be gifted with a photographic memory. He not only paints the past but he almost seems to return in his mind to that very situation that he wishes to impart upon the canvas. It is for this reason we see into Allen's paintings from the perspective of a child. Each experience he paints contains almost every significant detail from that moment and almost every moment he paints was seen in his childhood. Possibly one of the most common and striking revelations of this recall is that many of his paintings of the inside of his grandparents cabin are painted from the perspective of lying on a bed. This is not only revealed by the low perspective from which the canvas is obviously painted, but amazingly enough by the appearance of a cast iron rung which cuts across the corner foreground of the canvas so naturally that, unless it is pointed out, remains unnoticed by the viewer. Once one is attuned to the nature of Allen's recall you begin to see the child's perspective everywhere. The tiny cabin he was raised in often appears large and spacious (as a child would perceive it). Suddenly the many canvases that seem to be painted from an overhead perspective, become understandable when we see the small boy climbing up a tree. Gates, hay wagons, and fences often cut right across the foreground of a painting regardless of what they might seem to obscure, leaving no sense that they might be out of place.

Images Waiting to be Revealed

A second and equally fascinating aspect of Allen Sapp's approach to painting is in the execution itself. Almost every artist whose style is realism (schooled or otherwise) is familiar with and uses a technique called "a thumbnail sketch". This technique of drawing a few small preliminary sketches allows the artist to anticipate and plan how he will execute the final draft of his painting. Even artists whose ability or technique is such that they may not require a thumbnail sketch will sketch and rearrange a draft version of the painting directly on the canvas in charcoal. Sketching is the way most artists visualize and formulate what they see in their minds. It is the way an idea takes on substance and can be altered, corrected and rearranged. Even when an artist has immediately before him a subject or the landscape, he inevitably is required to make an initial sketch to ensure good execution. Allen Sapp uses neither photograph nor live subjects; he does not make sketches, nor does he draw a single line on his canvas in preparation. " I have to think here, " Allen says, tapping his temple, " before I can paint it here," he explains, pointing to an imaginary canvas. Somehow after he has thought and returned to that time and place he knew, he picks up the brush and begins. Initially, only meaningless forms and shapes appeared on his canvas. Their purpose remains obscure to an observer. Even their placement seems random. Each shape and form is executed with certainty and decisiveness; there is no timidity in his application. To watch Sapp paint is to begin to understand Michelangelo when he described his own work as not sculpting forms and figures but discovering and releasing in each marble block the figure that lives within. Stroke after stroke seems to pull the canvas into its own vivid reality making each form and shape reveal something new and unexpected. From what seemed at first to be unnatural shapes and forms come images of men working, horses pulling, or people playing. Allen appears not to be painting a memory at all, but completing the details of an image already present on the canvas longing to take form.

Each image is real . . . together they make up the life of Allen Sapp

"Sapp, more than any other Indian artist, is able to infuse his canvases with a definitive sense of mood, feeling and emotion for his subjects," says American sociologist John Anson Warner. This 'sense of mood' Sapp so effectively transmits is connected to how he recalls the images he paints. Allen does not paint fragments of stolen images from out of the past, rather each painting is a living experience which remains dynamic and alive both within and beyond the canvas itself. This is most effectively revealed by Allen Sapp himself when he was asked to describe one of his works. He began to describe a painting of two men driving sleighs on a road, the sleighs having paused beside one another. Rather than describing the technique or even the content, Allen begins to recall word for word the conversation of the two men who are speaking with one another how one man is taking wood to sell to a white man and the other tells him to ask the white man if he needs any more because he had some to sell also. It is not uncommon for Allen, while describing a painting to refer to a cabin or someone who is outside the painting, indicating that the other cabin or person would be "right over here" while pointing at the wall beside the painting. Through this we are able to see that each painting becomes a vivid event returned to, and relived by Allen, opening to the viewer something much greater than a single image of the past. It is for this reason that "Allen Sapp more than any other Indian artist is able to infuse his canvas" with that "emotion and feeling" . With this in mind we are able to view Allen Sapp's paintings in a new light we begin to fully appreciate how his work truly is an intimate portrait of his own people. Every character is real. Every image drawn is from experiences that together make up the life of Allen Sapp. Sapp's work is powerful because he has so successfully brought to his canvas a real sense of the Cree people and their past. In telling of a simple, quiet people and their determination to survive, his work over the years has depicted almost every aspect of life Allen ever knew on the reserve. His simple titles themselves become an intimate part of each painting and again reveal just how personal this portrait of his people is: "Sometimes I Would Sleep in my Grandmother's Bed", "John Bears Horses" , or "My Friend's Place at the Red Pheasant Reserve a Long Time Ago". It may well be possible that the power and success of Sapp's canvases is far beyond how he depicts the Cree of the past. Allen Sapp's portraits of his people seem to pull images from the past and connect them intimately with the present, providing a bridge and opening our eyes not only to a people who "lived long ago" but to a people alive and well, living all around us.

|

|

|

" I can't write a story or tell one in the white man's |

As Florence Pratt observed, "A fact too often missed is that Sapp's work depicts what is still common to the Cree Indian today." What may even be less obvious is how much of what Sapp depicts has a common root in us all. His love of family, the value he places in community, the importance of helping one another, these are memories of a way of life and value system our parents and grandparents have shared. In a highly complex, individualistic and commercial society we have moved far from this "old way" of life; but somehow we inwardly long for its simplicity and beauty. It is through this longing that we are all to be touched by Sapp's work, finding in it a place and a people not so different than ourselves. From the very beginning, Doctor Allan Gonor seemed to grasp that, " There is a universal quality to Allen s work. It reaches beyond the singular experience of the Cree to encompass a description of many Canadians." In a sense the people Allen Sapp so sensitively portrays extend far beyond the Cree to all persons who can find in his work something of themselves.

December 31, 2015

City Mourns Passing of Renowned Artist

Allen Fredrick Sapp, January 2, 1928 – December 29, 2015

The City of North Battleford and the Allen Sapp Gallery - The Gonor Collection, sadly announce the passing of our beloved friend, for which our gallery is dedicated to, world renowned, Cree Artist, Allen Sapp. Sapp passed away peacefully in his sleep on Tuesday, December 29, 2015, in North Battleford,

Saskatchewan, Canada. We extend our heartfelt condolences to Allen Sapp’s family and friends.

Allen Sapp is one of Canada’s most distinguished artists and has received many of the nation’s highest honours and awards including:

1975: Elected to the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts.

1985: One of the first eight recipients of the Saskatchewan Award of Merit.

1987: Appointed an Officer of the Order of Canada.

1996: Recipient of a Lifetime Award for Excellence in the Arts from the Saskatchewan Arts Board.

1998: Awarded with an Honourary Doctorate Degree from the University of Regina

1999: Recipient of the National Aboriginal Achievement Award.

2003: Received the Governor General's Literary Award for his illustrations in the children's book The Song Within My Heart.

2005: Through the Eyes of the Cree and Beyond: The Art of Allen Sapp – A Story of a People, which won the Saskatchewan Book of the Year Award in the First Nations Category.

Sapp’s work and life story has also been the subject of numerous books and television documentaries such as the National Film Board of Canada’s Colours of Pride, and the CBC’s On the Road Again and Allen Sapp, By Instinct a Painter.

Books include A Cree Life, by John Warner, Two Spirits Soar, by W.P. Kinsella, and Through the Eyes of the Cree; The Art of Allen Sapp – A Story of a People – produced by the Allen Sapp Gallery.

In 1989, The City of North Battleford opened a public art gallery in honour of Dr. Allan Gonor and Allen Sapp and dedicated it to the art of Allen Sapp. A donation of Allen’s paintings by Dr. Allan Gonor and his wife Ruth Gonor comprise the foundation of the art collection at the gallery.

Allen was born on January 2, 1928 on the Red Pheasant Reserve in north central Saskatchewan to Alex and Agnes Sapp. Allen was a weak and sickly child whose mother also suffered from sickness and eventually died of tuberculosis while Allen was away at residential school. Allen was raised by his maternal grandparents, Albert and Maggie Soonias on the Red Pheasant Reserve where his grandfather operated a ranch and where his grandmother, Maggie Soonias, cared for him. The memory of this tender relationship spawned some of Allen’s finest and most sensitive works.

In 1963, after the death of his grandparents, Allen, with his wife and young son, moved to North Battleford so that Allen could pursue a career as a professional artist. Allen did what many artists do and that was to look at the commercial viability of his art and as a result he painted what he thought other people would be interested in buying. One day Allen timidly walked into a medical clinic in

North Battleford in hope of selling some of his art to the doctors that worked there. It was at this time, that Allen Sapp met Dr. Allan Gonor who saw immediately the significance and possibilities of Sapp’s work. This meeting was the beginning of their friendship, one that would change both men’s lives. Dr.

Gonor encouraged Allen to “paint what he knew”, which was, “life on the Red Pheasant Reserve”. Allen didn’t hesitate at the chance, and as a result a floodgate of memories poured out onto canvas. Dr. Gonor continued to mentor Allen, helping him to develop his professional resources, and on Allen’s behalf, Dr. Gonor sought assistance from other arts professionals. The result of this friendship and partnership has made Allen Sapp one of Canada’s most prolific and preeminent artists of all time, having exhibited in London, England and extensively throughout North America.

For the most part Allen was a self-taught artist. He is said to have worked “instinctively” with a photographic memory; painting the pictures he sees in his mind. His paintings tell a personal story, but many appreciate them for their ability to go beyond that and represent a generation of Cree people and many other prairie inhabitants of the same era. His work allows viewers to reflect upon the hardships of the past and remember friendship and family as well as a less complicated way of life. Allen’s paintings masterfully depict First Nations culture, the simple elegance of rural life, and the beauty of Saskatchewan.

Allen Sapp was predeceased by his wife Margaret (Berryman) Sapp, his son, David Sapp, David’s mother and Allen’s first wife, Margaret Paskemin Whitford, his grandparents Albert and Maggie Soonias, his parents Alex and Agnes Sapp, his siblings who died as children, Julia, Virginia, John, and Henry. He is survived by his brother Simon Sapp, sister-in-law Theresa Sapp, and his sister Stella

Sapp, as well as numerous nieces, nephews and extended family. He is also survived by his adopted daughter, Faye Delorme, and the Merasty and Delorme Family.

A Wake was be held at the Chief Glen Keskotagen Memorial Hall - Red Pheasant Cree Nation. The funeral took place at the same location Friday January 1, 2016 at 11:00 a.m.

For more information:

Leah Garven, Curator/Manager of Galleries, 306-445-1760

© 2010 - Allen Sapp Gallery - Web Design by M.R. Website Development Studio